Student loan benefits more popular with workers than employers

"While a student loan benefit is the most-requested financial benefit, it’s only third on the priority list for HR professionals." Find out more in this article.

If you ask them, 78 percent of employees laboring under a load of student debt will tell you that they want their bosses to provide a student loan benefit that will help them dig out.

Bosses, not so much. While a student loan benefit is the most-requested financial benefit, according to an HRDive report, it’s only third on the priority list for HR professionals.

Related: The problem with student-loan repayment benefits

It’s not just younger workers who want it, either. The 78 percent of employees who wish their jobs came with a student loan benefit includes 65 percent of workers over age 55 who have problems with current or future loan debt.

The report points to a CommonBond study that finds student loan benefits not only help to keep employees on the payroll and even better their job performance, but they also help in recruiting new talent. The study finds that 75 percent of all workers have paid for their own education via student loans, and 21 percent plan to take out student loans for a child or another family member in the next five years.

Oh, and another disconnect between boss and worker: while 75 percent of HR executives think their benefits offerings are innovative, only 50 percent of workers agree.

Money, of course, is a big worry for workers—and it’s not all about salary, with 44 million Americans weighed down by some $1.4 trillion in student debt. Worrying about lingering student loans also cuts productivity at work, in addition to subjecting workers to increasing stress, so it’s really an employer’s problem too.

Not only do students owe an average of more than $25,000 by graduation, figures from The Student Loan Report indicate that the loan default rate and delinquency rates are more than 10 percent and 5 percent, respectively—not exactly conducive to either peace of mind or high productivity at work. So employers are increasingly getting involved, considering tuition payment programs for employees who want to pursue a degree or add new skills.

And that can help both groups as employers become increasingly desperate for a more skilled employee base. It also helps employers as employee stress falls, potentially cutting health care costs as well and making workers more productive.

Source:

Satter M. (7 May 2018). "Student loan benefits more popular with workers than employers" [web blog post]. Retrieved from address https://bit.ly/2wi9yA0

Fresh Brew With Kevin Hagerty

Welcome to our brand new segment, Fresh Brew, where we will be exploring the delicious coffees, teas, and snacks of some of our employees! You can look forward to our Fresh Brew blog post on the first Friday of every month.

“Try to save what you can. You’ll be glad you did later.”

Kevin has been a Financial Advisor for 18 years specializing in financial planning solutions.

He and his wife Lori enjoy spending their free time involved in various school and sporting events with their two sons. They also enjoy spending time visiting family on the shores of Northern Michigan’s Lakes and working on various projects around the house like landscaping.

Favorite Brew

Flavored Coffee

“I just like it! Highly recommend Carabello Coffee for your flavored coffee needs!”

Pre-existing Conditions and Medical Underwriting in the Individual Insurance Market Prior to the ACA

Data provided through two, large government surveys, The National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) and the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), Kaiser Family Foundation addresses the risk factors involved in repealing and repealing ACA.

Before private insurance market rules in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) took effect in 2014, health insurance sold in the individual market in most states was medically underwritten.1 That means insurers evaluated the health status, health history, and other risk factors of applicants to determine whether and under what terms to issue coverage. To what extent people with pre-existing health conditions are protected is likely to be a central issue in the debate over repealing and replacing the ACA. This brief reviews medical underwriting practices by private insurers in the individual health insurance market prior to 2014, and estimates how many American adults could face difficulty obtaining private individual market insurance if the ACA were repealed or amended and such practices resumed. We examine data from two large government surveys: The National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) and the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), both of which can be used to estimate rates of various health conditions (NHIS at the national level and BRFSS at the state level). We consulted field underwriting manuals used in the individual market prior to passage of the ACA as a reference for commonly declinable conditions.

Estimates of the Share of Adults with Pre-Existing Conditions

We estimate that 27% of adult Americans under the age of 65 have health conditions that would likely leave them uninsurable if they applied for individual market coverage under pre-ACA underwriting practices that existed in nearly all states. While a large share of this group has coverage through an employer or public coverage where they do not face medical underwriting, these estimates quantify how many people could be ineligible for individual market insurance under pre-ACA practices if they were to ever lose this coverage. This is a conservative estimate as these surveys do not include sufficient detail on several conditions that would have been declinable before the ACA (such as HIV/AIDS, or hepatitis C). Additionally, millions more have other conditions that could be either declinable by some insurers based on their pre-ACA underwriting guidelines or grounds for higher premiums, exclusions, or limitations under pre-ACA underwriting practices. In a separate Kaiser Family Foundation poll, most people (53%) report that they or someone in their household has a pre-existing condition. A larger share of nonelderly women (30%) than men (24%) have declinable preexisting conditions. We estimate that 22.8 million nonelderly men have a preexisting condition that would have left them uninsurable in the individual market pre-ACA, compared to 29.4 million women. Pregnancy explains part, but not all of the difference. The rates of declinable pre-existing conditions vary from state to state. On the low end, in Colorado and Minnesota, at least 22% of non-elderly adults have conditions that would likely be declinable if they were to seek coverage in the individual market under pre-ACA underwriting practices. Rates are higher in other states – particularly in the South – such as Tennessee (32%), Arkansas (32%), Alabama (33%), Kentucky (33%), Mississippi (34%), and West Virginia (36%), where at least a third of the non-elderly population would have declinable conditions.

| Table 1: Estimated Number and Percent of Non-Elderly People with Declinable Pre-existing Conditions Under Pre-ACA Practices, 2015 | ||

| State | Percent of Non-Elderly Population | Number of Non-Elderly Adults |

| Alabama | 33% | 942,000 |

| Alaska | 23% | 107,000 |

| Arizona | 26% | 1,043,000 |

| Arkansas | 32% | 556,000 |

| California | 24% | 5,865,000 |

| Colorado | 22% | 753,000 |

| Connecticut | 24% | 522,000 |

| Delaware | 29% | 163,000 |

| District of Columbia | 23% | 106,000 |

| Florida | 26% | 3,116,000 |

| Georgia | 29% | 1,791,000 |

| Hawaii | 24% | 209,000 |

| Idaho | 25% | 238,000 |

| Illinois | 26% | 2,038,000 |

| Indiana | 30% | 1,175,000 |

| Iowa | 24% | 448,000 |

| Kansas | 30% | 504,000 |

| Kentucky | 33% | 881,000 |

| Louisiana | 30% | 849,000 |

| Maine | 29% | 229,000 |

| Maryland | 26% | 975,000 |

| Massachusetts | 24% | 999,000 |

| Michigan | 28% | 1,687,000 |

| Minnesota | 22% | 744,000 |

| Mississippi | 34% | 595,000 |

| Missouri | 30% | 1,090,000 |

| Montana | 25% | 152,000 |

| Nebraska | 25% | 275,000 |

| Nevada | 25% | 439,000 |

| New Hampshire | 24% | 201,000 |

| New Jersey | 23% | 1,234,000 |

| New Mexico | 27% | 332,000 |

| New York | 25% | 3,031,000 |

| North Carolina | 27% | 1,658,000 |

| North Dakota | 24% | 111,000 |

| Ohio | 28% | 1,919,000 |

| Oklahoma | 31% | 706,000 |

| Oregon | 27% | 654,000 |

| Pennsylvania | 27% | 2,045,000 |

| Rhode Island | 25% | 164,000 |

| South Carolina | 28% | 822,000 |

| South Dakota | 25% | 126,000 |

| Tennessee | 32% | 1,265,000 |

| Texas | 27% | 4,536,000 |

| Utah | 23% | 391,000 |

| Vermont | 25% | 96,000 |

| Virginia | 26% | 1,344,000 |

| Washington | 25% | 1,095,000 |

| West Virginia | 36% | 392,000 |

| Wisconsin | 25% | 852,000 |

| Wyoming | 27% | 94,000 |

| US | 27% | 52,240,000 |

| SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of data from National Health Interview Survey and the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. NOTE: Five states (MA, ME, NJ, NY, VT) had broadly applicable guaranteed access to insurance before the ACA. What protections might exist in these or other states under a repeal and replace scenario is unclear. | ||

At any given time, the vast majority of these approximately 52 million people with declinable pre-existing conditions have coverage through an employer or through public programs like Medicaid. The individual market is where people seek health insurance during times in their lives when they lack eligibility for job-based coverage or for public programs such as Medicare and Medicaid. In 2015, about 8% of the non-elderly population had individual market insurance. Over a several-year period, however, a much larger share may seek individual market coverage.2 This market is characterized by churn, as new enrollees join and others leave (often for other forms of coverage). For many people, the need for individual market coverage is intermittent, for example, following a 26th birthday, job loss, or divorce that ends eligibility for group plan coverage, until they again become eligible for group or public coverage. For others – the self-employed, early retirees, and lower-wage workers in jobs that typically don’t come with health benefits – the need for individual market coverage is ongoing. (Figure 1 shows the distribution of employment status among current individual market enrollees.) Prior to the ACA’s coverage expansions, we estimated that 18% of individual market applications were denied. This is an underestimate of the impact of medical underwriting because many people with health conditions did not apply because they knew or were informed by an agent that they would not be accepted. Denial rates ranged from 0% in a handful of states with guaranteed issue to 33% in Kentucky, North Carolina, and Ohio. According to 2008 data from America’s Health Insurance Plans, denial rates ranged from about 5% for children to 29% for adults age 60-64 (again, not accounting for those who did not apply).

Figure 1: Employment Status of Non-Group Enrollees, 2016

Medical Underwriting in the Individual Market Pre-ACA

Prior to 2014 medical underwriting was permitted in the individual insurance market in 45 states and DC. Applications for individual market policies typically included lengthy questionnaires about the health and risk status of the applicant and all family members to be covered. Typically, applicants were asked to disclose whether they were pregnant or contemplating pregnancy or adoption, and information about all physician visits, prescription medications, lab results, and other medical care received in the past year. In addition, applications asked about personal history of a series of health conditions, ranging from HIV, cancer, and heart disease to hemorrhoids, ear infections and tonsillitis. Finally, all applications included authorization for the insurer to obtain and review all medical records, pharmacy database information, and related information. Once the completed application was submitted, the medical underwriting process varied somewhat across insurers, but usually involved identification of declinable medical conditions and evaluation of other conditions or risk factors that warranted other adverse underwriting actions. Once enrolled, a person’s health and risk status was sometimes reconsidered in a process called post-claims underwriting. Although our analysis focuses on declinable medication conditions, each of these other actions is described in more detail below.

Declinable Medical Conditions

Before the ACA, individual market insurers in all but five states maintained lists of so-called declinable medical conditions. People with a current or past diagnosis of one or more listed conditions were automatically denied. Insurer lists varied somewhat from company to company, though with substantial overlap. Some of the commonly listed conditions are shown in Table 2.

| Table 2: Examples of Declinable Conditions In the Medically Underwritten Individual Market, Before the Affordable Care Act | |

| Condition | Condition |

| AIDS/HIV | Lupus |

| Alcohol abuse/ Drug abuse with recent treatment | Mental disorders (severe, e.g. bipolar, eating disorder) |

| Alzheimer’s/dementia | Multiple sclerosis |

| Arthritis (rheumatoid), fibromyalgia, other inflammatory joint disease | Muscular dystrophy |

| Cancer within some period of time (e.g. 10 years, often other than basal skin cancer) | Obesity, severe |

| Cerebral palsy | Organ transplant |

| Congestive heart failure | Paraplegia |

| Coronary artery/heart disease, bypass surgery | Paralysis |

| Crohn’s disease/ ulcerative colitis | Parkinson’s disease |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)/emphysema | Pending surgery or hospitalization |

| Diabetes mellitus | Pneumocystic pneumonia |

| Epilepsy | Pregnancy or expectant parent |

| Hemophilia | Sleep apnea |

| Hepatitis (Hep C) | Stroke |

| Kidney disease, renal failure | Transsexualism |

| SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation review of field underwriting guidelines from Aetna (GA, PA, and TX), Anthem BCBS (IN, KY, and OH), Assurant, CIGNA, Coventry, Dean Health, Golden Rule, Health Care Services Corporation (BCBS in IL, TX) HealthNet, Humana, United HealthCare, Wisconsin Physician Service. Conditions in this table appeared on declinable conditions list in half or more of guides reviewed. NOTE: Many additional, less-common disorders also appearing on most of the declinable conditions lists were omitted from this table. | |

Our analysis of rates of pre-existing conditions in this brief focuses on those conditions that would likely be declinable, based on our review of pre-ACA underwriting documents. Our analysis is limited – and our results are conservative – because NHIS and BRFSS questionnaires do not address some of the conditions that were declinable, and in some cases the questions that do relate to declinable conditions were too broad for inclusion. See the methodology section for a list of conditions included in the analysis. In addition to declinable conditions, many insurers also maintained a list of declinable medications. Current use of any of these medications by an applicant would warrant denial of coverage. Table 3 provides an example of medications that were declinable in one insurer prior to the ACA. Our analysis does not attempt to account for use of declinable medications.

| Table 3: Declinable Medications | ||

Anti-Arthritic Medications

|

Anti-Diabetic Medications

|

Medications for HIV/AIDS or Hepatitis

|

Anti-Cancer Medications

|

Anti-Psychotics, Autism, Other Central Nervous System Medications

|

|

Anti-Coagulant/Anti-Thrombotic Medications

|

Miscellaneous Medications

|

|

| SOURCE: Blue Cross Blue Shield of Illinois, Product Guide for Agents | ||

Some individual market insurers also developed lists of ineligible occupations. These were jobs considered sufficiently high risk that people so employed would be automatically denied. In addition, some would automatically deny applicants who engaged in certain leisure activities and sports. Table 4 provides an example of declinable occupations from one insurer prior to the ACA. Our analysis does not attempt to account for declinable occupations.

| Table 4: Ineligible Occupations, Activities | ||

| Active military personnel | Iron workers | Professional athletes |

| Air traffic controller | Law enforcement/detectives | Sawmill operators |

| Aviation and air transportation | Loggers | Scuba divers |

| Blasters or explosive handlers | Meat packers/processors | Security guards |

| Bodyguards | Mining | Steel metal workers |

| Crop dusters | Nuclear industry workers | Steeplejacks |

| Firefighters/EMTs | Offshore drillers/workers | Strong man competitors |

| Hang gliding | Oil and gas exploration and drilling | Taxi cab drivers |

| Hazardous material handlers | Pilots | Window washers |

| SOURCE: Preferred One Insurance Company Individual and Family Insurance Application Form | ||

Other Adverse Underwriting Actions

Beyond the declinable conditions, medications and occupations, underwriters also examined individual applications and medical records for other conditions that could generate significant “losses” (claims expenses.) Among such conditions were acne, allergies, anxiety, asthma, basal cell skin cancer, depression, ear infections, fractures, high cholesterol, hypertension, incontinence, joint injuries, kidney stones, menstrual irregularities, migraine headaches, overweight, restless leg syndrome, tonsillitis, urinary tract infections, varicose veins, and vertigo. One or more adverse medical underwriting actions could result for applicants with such conditions, including:

- Rate-up – The applicant might be offered a policy with a surcharged premium (e.g. 150 percent of the standard rate premium that would be offered to someone in perfect health)

- Exclusion rider – Coverage for treatment of the specified condition might be excluded under the policy; alternatively, the body part or system affected by the specified condition could be excluded under the policy. Exclusion riders might be temporary (for a period of years) or permanent

- Increased deductible – The applicant might be offered a policy with a higher deductible than the one originally sought; the higher deductible might apply to all covered benefits or a condition-specific deductible might be applied

- Modified benefits – The applicant might be offered a policy with certain benefits limited or excluded, for example, a policy that does not include prescription drug coverage.

In some cases, individuals with these conditions might also be declined depending on their health history and the insurer’s general underwriting approach. For example, field underwriting guides indicated different underwriting approaches for an applicant whose child had chronic ear infections:

- One large, national insurer would issue standard coverage if the child had fewer than five infections in the past year or ear tubes, but apply a 50% rate up if there had been more than 4 infections in the prior year;

- Another insurer, which used a 12-tier rate system, would issue coverage at the second most favorable rate tier if the child had just one infection in the prior year or ear tubes, at the fifth rate tier if there had been 2-3 infections during the prior year, and at the seventh tier if there had been 4 or more infections; for some conditions, this company’s rating might depend on the plan deductible – applicants with history of ear infections would be offered the second rating tier for policies with a deductible of $5,000 or higher;

- Another insurer would issue standard coverage if the child had just one infection in the prior year or if ear tubes had been inserted more than one-year prior, apply a rate up if there were two infections in the prior year, and decline the application if there were three or more infections;

- Another insurer would issue standard coverage if the child had fewer than 3 infections in the past year, but issue coverage with a condition specific deductible of $5,000 if there had been 3 or more infections or if ear tubes had been inserted.

In a 2000 Kaiser Family Foundation study of medical underwriting practices, insurers were asked to underwrite hypothetical applicants with varying health conditions, from seasonal allergies to situational depression to HIV. Results varied significantly for less serious conditions. For example, the applicant with seasonal allergies who made 60 applications for coverage was offered standard coverage 3 times, declined 5 times, offered policies with exclusion riders or other benefit limits 46 times (including 3 offers that excluded coverage for her upper respiratory system), and policies with premium rate ups (averaging 25%) 6 times.

Pre-existing Condition Exclusion Provisions

In addition to medical screening of applicants before coverage was issued, most individual market policies also included more general pre-existing condition exclusion provisions which limited the policy’s liability for claims (typically within the first year) related to medical conditions that could be determined to exist prior to the coverage taking effect.3

The nature of pre-existing condition exclusion clauses varied depending on state law. In 19 states, a health condition could only be considered pre-existing if the individual had actually received treatment or medical advice for the condition during a “lookback” period prior to the coverage effective date (from 6 months to 5 years). In most states, a pre-existing condition could also include one that had not been diagnosed but that produced signs or symptoms that would prompt an “ordinarily prudent person” to seek medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. In 8 states and DC, conditions that existed prior to the coverage effective date – including those that were undiagnosed and asymptomatic – could be considered pre-existing and so excluded from coverage under an individual market policy. For example, a congenital condition in a newborn could be considered pre-existing to the coverage effective date (the baby’s birth date) and excluded from coverage. About half of the states required individual market insurers to reduce pre-existing condition exclusion periods by the number of months of an enrollee’s prior coverage.

Unlike exclusion riders that limited coverage for a specified condition of a specific enrollee, pre-existing condition clauses were general in nature and could affect coverage for any applicable condition of any enrollee. Pre-existing condition exclusions were typically invoked following a process called post-claims underwriting. If a policyholder would submit a claim for an expensive service or condition during the first year of coverage, the individual market insurer would conduct an investigation to determine whether the condition could be classified as pre-existing. In some cases, post-claims underwriting might also result in coverage being cancelled. The investigations would also examine patient records for evidence that a pre-existing condition was known to the patient and should have been disclosed on the application. In such cases, instead of invoking the pre-existing condition clause, an issuer might act to rescind the policy, arguing it would have not issued coverage in the first place had the pre-existing condition been disclosed.

Discussion

The Affordable Care Act guarantees access to health insurance in the individual market and ends other underwriting practices that left many people with pre-existing conditions uninsured or with limited coverage before the law. As discussions get underway to repeal and replace the ACA, this analysis quantifies the number of adults who would be at risk of being denied if they were to seek coverage in the individual market under pre-ACA rules. What types of protections are preserved for people with pre-existing conditions will be a key element in the debate over repealing and replacing the ACA. We estimate that at least 52 million non-elderly adult Americans (27% of those under the age of 65) have a health condition that would leave them uninsurable under medical underwriting practices used in the vast majority of state individual markets prior to the ACA. Results vary from state-to-state, with rates ranging around 22 – 23% in some Northern and Western states to 33% or more in some southern states. Our estimates are conservative and do not account for a number of conditions that were often declinable (but for which data are not available), nor do our estimates account for declinable medications, declinable occupations, and conditions that could lead to other adverse underwriting practices (such as higher premiums or exclusions). While most people with pre-existing conditions have employer or public coverage at any given time, many people seek individual market coverage at some point in their lives, such as when they are between jobs, retired, or self-employed. There is bipartisan desire to protect people with pre-existing conditions, but the details of replacement plans have yet to be ironed out, and those details will shape how accessible insurance is for people when they have health conditions.

Methods

To calculate nationwide prevalence rates of declinable health conditions, we reviewed the survey responses of nonelderly adults for all question items shown in Methods Table 1 using the CDC’s 2015 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). Approximately 27% of 18-64 year olds, or 52 million nonelderly adults, reported having at least one of these declinable conditions in response to the 2015 survey. The CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) relies on the medical condition modules of the annual NHIS for many of its core publications on the topic; therefore, we consider this survey to be the most accurate means to estimate both the nationwide rate and weighted population. Since the NHIS does not include state identifiers nor sufficient sample size for most state-based estimates, we constructed a regression model for the CDC’s 2015 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) to estimate the prevalence of any of the declinable conditions shown in Methods Table 1 at the state level. This model relied on three highly significant predictors: (a) respondent age; (b) self-reported fair or poor health status; (c) self-report of any of the overlapping variables shown in the left-hand column of Methods Table 1. Across the two data sets, the prevalence rate calculated using the analogous questions (i.e. the left-hand column of Methods Table 1) lined up closely, with 20% of 18-64 year old survey respondents reporting at least one of those declinable conditions in the 2015 NHIS and 21% of 18-64 year olds in the 2015 BRFSS. Applying this prediction model directly to the 2015 BRFSS microdata yielded a nationwide prevalence of any declinable condition of 28%, a near match to the NHIS nationwide estimate of 27%.

| Methods Table 1: Declinable Medical Conditions Available in Survey Microdata | |

| Declinable Condition Questions Available in both the 2015 National Health Interview Survey and also the 2015 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System | Declinable Condition Questions Available in only the 2015 National Health Interview Survey |

| Ever had CHD | Melanoma Skin Cancer |

| Ever had Angina | Any Other Heart Condition |

| Ever had Heart Attack | Crohn’s Disease or Ulcerative Colitis |

| Ever had Stroke | Epilepsy |

| Ever had COPD | Difficulty Due to Mental Retardation |

| Ever had Emphysema | Difficulty Due to Cerebral Palsy |

| Chronic Bronchitis in past 12 months | Difficulty Due to Senility |

| Ever had Non-Skin Cancer | Difficulty Due to Depression |

| Ever had Diabetes | Difficulty Due to Endocrine Problem |

| Weak or Failing Kidneys | Difficulty Due to Blood Forming Organ Problem |

| BMI > 40 | Difficulty Due to Drug / Alcohol / Substance Abuse |

| Pregnant | Difficulty Due to Schizophrenia, ADD, or Bipolar Disorder |

In order to align BRFSS to NHIS overall statistics, we then applied a Generalized Regression Estimator (GREG) to scale down the BRFSS microdata’s prevalence rate and population estimate to the equivalent estimates from NHIS, 27% and 52 million. Since the regression described in the previous paragraph already predicted the prevalence rate of declinable conditions in BRFSS by using survey variables shared across the two datasets, this secondary calibration solely served to produce a more conservative estimate of declinable conditions by calibrating BRFSS estimates to the NHIS. After applying this calibration, we calculated state-specific prevalence rates and population estimates off of this post-stratified BRFSS sample. The programming code, written using the statistical computing package R v.3.3.2, is available upon request for people interested in replicating this approach for their own analysis.

This article was written by Gary Claxton, Cynthia Cox, Anthony Damico, Larry Levitt and Karen Pollitz on Kaiser Family Foundation. Published: Dec 12, 2016

Proposals for Insurance Options That Don’t Comply with ACA Rules: Trade-offs In Cost and Regulation

Now in the fifth year of implementation, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) standards for non-group health insurance require health plans to provide major medical coverage for essential health benefits (EHB) with limits on deductibles and other cost sharing. In addition, ACA standards prohibit discrimination by non-group plans: pre-existing conditions cannot be excluded from coverage and eligibility and premiums cannot vary based on an individual’s health status. The ACA also created income-based subsidies to reduce premiums (premium tax credits, or APTC) and cost-sharing for eligible individuals who purchase non-group plans, called qualified health plans (QHPs), through the Marketplace. ACA-regulated non-group plans can also be offered outside of the Marketplace, but are not eligible for subsidies.

New: A look at the tradeoffs in costs and protections involved in four proposed health plan alternatives that would operate outside the ACA’s rules and regulations

Individual market premiums were relatively stable during the first three years of ACA implementation, then rose substantially in each of 2017 and 2018. Last year, nearly 9 million subsidy-eligible consumers who purchased coverage through the Marketplace were shielded from these increases; but another nearly 7 million enrollees in ACA compliant plans, who do not receive subsidies, were not. Bipartisan Congressional efforts to stabilize individual market premiums – via reinsurance and other measures – were debated in the fall of 2017 and the spring of 2018, but not adopted. Meanwhile, opponents of the ACA at the federal and state level have proposed making alternative plan options available that would be cheaper, in terms of monthly premiums, for at least some people because plans would not be required to meet some or all standards for ACA-compliant plans. This brief explains state and federal proposals to create a market for more loosely-regulated health insurance plans outside of the ACA regulatory structure.

Background

When ACA Marketplaces first opened in 2014, on average, the cost of the benchmark silver QHP was lower than many had predicted. Many insurers underpriced QHPs at the outset, either because they couldn’t accurately predict the cost of providing coverage to a new population under new ACA rules, or to aggressively compete for market share, or both. As a result, insurers offering ACA-compliant policies generally lost money in 2014-2016. In the fall of 2016, for the 2017 coverage year, most issuers implemented a substantial corrective premium increase for their benchmark QHP – on average, a 21% increase for a 40-year-old consumer. This increase, along with growing experience with new market rules, allowed many insurers to regain profitability in 2017, and, going forward, stabilization of QHP rates might otherwise have been expected.

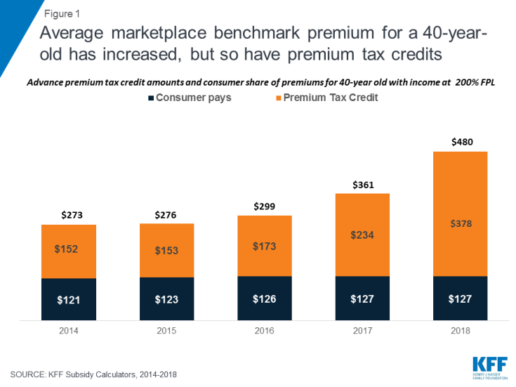

Instead, though, a new wave of uncertainty arose last year as Congress debated repeal of the ACA and as the Trump Administration threatened administrative actions with the stated intent of undermining the program, including by ending reimbursement to insurers for required cost-sharing reductions (CSRs) that, by law, they must offer low-income enrollees in silver QHPs. The value of CSRs was estimated by CBO to be $9 billion for 2018. To compensate for the lost reimbursement, most insurers significantly increased 2018 premiums for silver level QHPs, through which cost sharing subsidies are delivered. Largely due to this so-called “silver load” pricing strategy, the average benchmark silver QHP premium for a 40-year-old rose another 33% for the 2018 coverage year. (Figure 1) Premiums for bronze and gold plans rose more slowly, but still substantially given uncertainty on a number of issues, including whether the ACA’s individual mandate would be enforced.

https://bit.ly/2wctNPc

Figure 1: Average marketplace benchmark premium for a 40-year-old has increased, but so have premium tax credits

For consumers who are eligible for APTC and who buy the benchmark silver plan (or a less expensive plan) through the Marketplace, subsidies absorb annual premium increases and the net cost of coverage has remained relatively unchanged from 2014 through today. Roughly 85% of Marketplace participants in 2017 were eligible for APTC. (Figure 2) However, for the 15% of Marketplace participants who were not eligible for subsidies, and for another roughly 5 million individuals who bought ACA compliant plans outside of the Marketplace, these consecutive annual rate increases threatened to make coverage unaffordable. That threat was even greater in some areas, where 2018 QHP rate increases were much higher than the national average.

https://bit.ly/2joFWY4

Figure 2: Most in ACA-compliant plans are protected from rate increases by premium subsidies

Looking ahead, another round of significant premium increases is possible for the 2019 coverage year. A new source of uncertainty arose when Congress voted to end the ACA’s individual mandate penalty, effective in 2019. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated repeal of the mandate would fuel adverse selection – as some younger, healthier consumers might be more likely to forego coverage – and average premiums in the non-group market would increase by about 10 percent in most years of the decade, on top of increases due to other factors such as health care cost growth.

ACA opponents have argued QHP premium increases reflect a failure of the federal law. As an alternative, some have proposed different kinds of health plan options to offer premium relief to consumers who need non-group coverage but who are not eligible for premium subsidies, primarily by relaxing rules governing required benefits, coverage of pre-existing conditions, and/or community rating. These include:

Short-Term, Limited Duration Health Insurance Policies

In 2018 the Trump Administration proposed a new draft regulation that would promote the sale of short-term, limited duration health insurance policies that offer less expensive coverage because they are not subject to ACA market rules.

Short-term limited-duration health insurance policies (STLD), sometimes referred to as limited-duration non-renewable policies, are designed to provide temporary health coverage for people who are uninsured or are losing their existing coverage but expect to become eligible for other, more permanent coverage in the near future. Historically, people who have used these policies include graduating students losing coverage through their parents or their school, people with a short interval between jobs, or newly hired employee subject to a waiting period before they are eligible for coverage from their job. Because these policies are not intended to provide long-term protection (they generally cannot be renewed when their term ends), they are lightly regulated by states and are exempt from many of the standards generally applicable to individual health insurance policies. They also are specifically exempt under the ACA from federal standards for individual health insurance coverage, including the essential health benefits, guaranteed availability and prohibitions against pre-existing condition exclusions and health-status rating. These differences can make them considerably less expensive (for those healthy enough to qualify to buy them) than ACA compliant plans.

STLDs are similar to major medical policies in that they typically cover both hospitalization and at least some outpatient medical services, but unlike ACA-compliant policies, they often have significant benefit and eligibility limitations. STLD policies often either exclude are have significant limitations on benefits for mental health and substance abuse, do not have coverage for maternity services, and have limited or no coverage for prescription drugs. Policies also generally have dollar limits on all benefits or specific benefits and may have deductibles and other cost sharing that is much higher than permitted in ACA-compliant plans. Insurers of STLD policies typically use medically underwriting, which means that they can turn down applicants with health problems or charge them higher premiums. Policies also exclude coverage for any benefits related to a preexisting health condition: a backstop for insurers in case a person with a health problem otherwise qualifies for coverage and seeks benefits. Because STLD policies are not renewable, people who become ill after their coverage begins are generally not able to qualify for a new policy when their coverage term ends.

Due to their lower premiums, some people have been purchasing STLD policies instead of ACA compliant plans. This has happened even though STLD policies are not considered minimum essential coverage, which means that people who purchase them do not satisfy the ACA mandate to have health insurance and may be subject to a tax penalty. In 2016, CMS expressed concern about these policies being sold as a type of “primary health insurance” and issued regulations shortening the maximum coverage period under federal law for STLD policies from less than 12 months to less than three months and prescribing a disclosure that must be provided to new applicants. The intent of the regulation was to limit sale of these policies to situations involving a short gap in coverage and to discourage their use a substitute for primary health insurance coverage. The rule took effect for policies issued to individuals on or after January 1, 2017. In February 2018, the Trump Administration issued a new proposed regulation to reinstate the “less than 12 months” maximum coverage term for STLD policies. The preamble to the proposed regulation specified that this would provide more affordable consumer choice for health coverage. For more information about STLD policies, see this issue brief.

Extending the coverage period for STLD policies back to just under a year is likely to make them a more attractive choice for healthier individuals concerned about the cost of ACA-compliant plans. This is particularly true beginning in 2019 when the individual mandate penalty ends and purchasers will no longer need to pay a penalty in addition to the premiums for these policies.

Under the ACA framework, STLD plans may provide a lower-cost alternative source of health coverage for people in good health. With ACA policies as a backup, people who purchase STLD policies and develop a health problem would not be able to renew their short-term policy at the end of its term, but would be able to elect an ACA-compliant plan during the next open enrollment.

It is possible, as one estimate concluded, that more healthy individual market participants may switch to short-term policies as a result. Such “adverse selection” would raise the average cost of covering remaining individuals in ACA-compliant plans, leading to further premium increases in those policies. For people with pre-existing conditions who do not qualify for subsidies, the rising cost of ACA-compliant coverage could challenge affordability, especially for people with pre-existing conditions who have incomes that make them ineligible for premium subsidies.

Association Health Plans

Another draft regulation proposed by the Trump Administration would permit small employers and self-employed individuals to buy a new type of association health plan coverage that does not have to meet all requirements applicable to other ACA-compliant small group and non-group health plans. While many types of health insurance are marketed though associations, including STLDs, hospital indemnity plans and cancer or other dread disease policies, current policy discussions about AHPs tend to focus on arrangements formed by groups of employers (called multiple employer welfare arrangements, or MEWAs) which could also offer group health insurance coverage to self-employed people without any employees (“sole proprietors”).

The U.S. Department of Labor recently proposed regulations under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) to expand the types of MEWAs that could offer health plans that would not be subject to certain ACA requirements. Under the draft regulation, AHPs – a type of MEWA – could offer health coverage to sole proprietors and to small businesses, but would be subject to large group health plan standards. Key ACA requirements for the non-group and small group market do not apply to large group health plans today, and so would not apply to AHP coverage sold to self-employed individuals or small employers. In particular, AHPs would not be required to cover essential health benefits; it would be possible under the proposed regulation for AHPs to offer policies that do not cover prescription drugs, for example.

Under the draft regulation, AHPs would be subject to a nondiscrimination standard that would prohibit basing eligibility or premiums on an enrollee’s health status. However, other ACA rating standards in the non-group and small group market would not apply; in particular, AHPs would be allowed to vary premiums by more than 3:1 for age and without limit based on gender, geography, and other factors such type of industry or occupation.

As a result, AHPs could provide self-employed individuals an alternative to individual health insurance that provides fewer benefits with more rating flexibility. As nearly one-third (31%) of individual market enrollees are self-employed, the impact of AHPs could be significant.

The draft regulation included other language related to state vs. federal regulatory authority over MEWAs, or AHPs. Currently, MEWAs are subject to a somewhat complex mix of regulatory provisions at the federal and state levels; the applicable standards vary depending on a number of things, including whether the MEWA is self-funded or provides benefits through insurance, whether the arrangement itself is considered to be sponsoring an employee benefit plan as defined in ERISA, the sizes of the employers participating in the arrangement, and how the states in which the arrangements operate approach MEWA regulation. The proposed rule generally leaves in place state authority over MEWAs/AHPs. However, the DOL requested comments on whether it should consider changes that would limit state regulation of self-funded AHPs to financial matters such as solvency and reserves, in effect, prohibiting states from regulating AHP rating and benefit design practices.

The degree of impact on individual health insurance markets will depend in part on the final rules, in particular whether the nondiscrimination provision is preserved and whether states retain current authority over AHPs.

Idaho Proposal for New State-Based Health Plans

In January 2018, pursuant to an executive order by Governor Otter, the Idaho Department of Insurance issued a bulletin outlining provisions of new individual health insurance products that insurance companies would be permitted to sell under state law. The new “State-Based Health Benefit Plans” would not have to comply with certain ACA requirements and, as a result, would likely be offered for premiums lower than those charged for ACA-compliant policies – at least for consumers who are younger and who don’t have pre-existing conditions.

State-Based Health Plans would be required to cover a package of health benefits and cost sharing that was less than that required for ACA-compliant plans. For example, certain essential health benefit categories, such as habilitation services and pediatric dental and vision, appear not to be required. In addition, ACA limits on cost sharing were not specified, and annual dollar limits on covered benefits could be applied. If consumers reach the annual dollar limit on coverage under a state-based plan, the insurer would be required to transfer their enrollment into an ACA-compliant plan.

In addition, state-based plans would not be allowed to deny applicants based on health status and could be sold year round, outside of Open Enrollment. However, State-Based plans could exclude coverage of pre-existing conditions for any individual who had experienced at least a 63-day break in coverage. These plans would also be permitted to vary premiums by a factor of 3:1 based on health status (prohibited by the ACA), and by 5:1 based on age (higher than the 3:1 ratio permitted by the ACA). In order to offer a State-Based Health Plan, insurers would also be required to offer at least one QHP through the Idaho Marketplace.

The bulletin required that state-based plans and exchange-certified plans must comprise a single risk pool, with a single index rate for all plans that does not account for differences in the health status of individuals who enroll, or are expected to enroll in a particular type of plan. However, the Academy of Actuaries noted that, because the two types of plans would not be competing under the same rules, “there would be, in effect, two risk pools – one for ACA coverage and one for state-based coverage. Premiums for ACA coverage would increase, threatening sustainability of the ACA market and its pre-existing condition protections.”

The Idaho State-Based Health Plan proposal is similar in many respects to an amendment offered by Senator Ted Cruz during the ACA repeal debate in 2017. The amendment, which was not enacted, would have allowed insurers that sell ACA-compliant marketplace plans to also offer other policies that could be medically underwritten and that would not have to meet other ACA standards. Although CBO did not estimate how the amendment would impact premiums or coverage, representatives of the insurance industry predicted that, “As healthy people move to the less-regulated plans, those with significant medical needs will have no choice but to stay in the comprehensive plans, and premiums will skyrocket for people with preexisting conditions. This would especially impact middle-income families that that are not eligible for a tax credit.”

The Idaho proposal appears to be not moving forward at this time. Recently, the director of the federal Center on Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) advised Idaho officials that these State-Based health plans would be in violation of federal law. Under the ACA, states do not have flexibility to authorize the sale of individual health insurance policies that do not meet federal minimum standards. In states that do not enforce federal minimum standards, the federal government is required to step in and enforce.

The CMS letter did generally express sympathy with Idaho’s approach, citing “damage caused by the [ACA],” and encouraged the state to pursue modified strategies to expand availability of more affordable plans that do not meet all ACA requirements. The letter specifically urged Idaho to consider promoting short-term policies as a legal alternative to ACA-compliant health plans, and it invited the State to develop other alternative strategies using ACA state waiver authority.

Farm Bureau Health Plans Exempt from State Regulation

A new Iowa law enacted this month would permit the sale of health coverage by the state’s Farm Bureau. The Farm Bureau is not a licensed health insurer. Under the new law, Farm Bureau health plans would be deemed to not be insurance and explicitly would not be subject to state insurance regulation. By extension, Farm Bureau plans also would not have to meet federal ACA standards for health insurance as these apply only to policies sold by state licensed health insurers.

The new Iowa law applies no other standards for Farm Bureau health plans – for example, it does not establish minimum benefit requirements, rating requirements, or rules prohibiting discrimination based on pre-existing health conditions. Appeal rights guaranteed to health insurance policyholders also would not apply to Farm Bureau enrollees, nor would state insurance solvency and other financial regulations. The law does require the Farm Bureau to administer coverage through a state licensed third party administrator, or TPA (expected to be Wellmark, Iowa’s Blue Cross Blue Shield insurer.) However, use of a TPA does not extend federal or state insurance law to the underlying Farm Bureau health plan.

The Iowa law closely resembles a Tennessee state law, enacted in 1993, which authorized the sale of health coverage by the Farm Bureau and deemed such coverage not to be health insurance subject to state regulation. In Tennessee, it has been reported that roughly 25,000 residents purchase non-group Farm Bureau health plans that are medically underwritten. (By comparison, more than 228,000 residents have ACA-compliant individual policies through the Marketplace this year.) Farm Bureau plan premiums can be as much as two-thirds lower than for ACA-compliant plans because the underwritten policies can and do deny coverage to people with pre-existing conditions. Adverse selection results, with sicker residents confined to the ACA-regulated market. An analysis of risk scores for state insurance markets finds that Tennessee’s individual market has one of the highest risk scores in the nation.

Since 2014, Tennessee residents who buy underwritten Farm Bureau health coverage are not considered to have “minimum essential coverage” and so may owe a tax penalty under the ACA individual mandate. However, this disincentive to purchase Farm Bureau plans in Tennessee and Iowa will end in 2019 when repeal of the mandate penalty takes effect.

Discussion

Each of these proposals follows a similar theme. Creating parallel insurance markets with different, lesser consumer protections, allows insurers to offer lower premiums and less coverage to people while they are healthy, leaving the ACA-regulated market with a sicker pool and higher premiums. Once repeal of the ACA individual mandate penalty takes effect in 2019, the net cost differential between regulated and less-regulated coverage will be even greater.

Premium subsidies in the ACA-regulated market will help to curb adverse selection, protecting people with lower incomes from the impact of higher premiums, and providing some continued stability in the reformed market. However, middle-income people who are not eligible for subsidies, and who have pre-existing conditions, will not have any meaningful new coverage choices under these proposals. Instead, the cost of health insurance that covers essential benefits and their pre-existing conditions will increase, potentially further pricing them out of affordable coverage altogether.

Source:

Pollitz K. (18 April 2018). "Proposals for Insurance Options That Don’t Comply with ACA Rules: Trade-offs In Cost and Regulation" [web blog post]. Retrieved from address https://kaiserf.am/2w89S3Z

Saxon's Go365 Clinic: A Can't Miss Wellness Event

In this installment of CenterStage, we are spotlighting our upcoming event, as presented by our Wellness Director, Abby Graham!

Saxon, along with Humana and HealthWorks, will host a wellness seminar about Humana’s wellness program on Wednesday, May 23. This exciting wellness clinic will aid employers in creating a more engaged workforce around wellness. Plus, there may be an awesome incentive involving a discount on insurance premiums, so keep reading!

Relationship Status - Going Strong

Humana is an insurance carrier represented by Saxon. Humana offers a personalized wellness and rewards program that we find to be exceptional for helping workplace environments create a great sense of community and health. HealthWorks is an outside vendor that works alongside Humana to provide wellness guidance and related services. HealthWorks will have a roundtable discussion explaining how they coordinate benefits with the Go365 program. With all three of us together at the event, employers will have the ability to have all their questions answered and have educational resources at their disposal.

Things to Look Forward to

“If you are someone in your company that is into wellness and is wanting to get others involved in a health initiative, then this event is for you! It will allow you to become an expert on Humana’s Go365 program and see why it is a fantastic incentive-based wellness program.” - Abby Graham

The event will feature several individual round tables, each one covering a different topic (see next page for topics). There will even be a 15% discount on premium insurance once you reach Gold Status in the program. The event is free to attend, and breakfast and lunch will be provided.

Sounds pretty great, right? If you are interested in saving money, increasing employee incentives, and creating a healthier workforce, be sure to sign up now to attend our Go365 seminar.

All questions and concerns regarding the event can be directed to Abby Graham at 513.334.0371 or send her an email via agraham@gosaxon.com. We can't wait to see you there!

What to Know in the Immigration Debate Now: “Queen-of-the-Hill”?

What will be the fate of those who dream to come to America? Explore the immigration debate in this article from SHRM.

Immigration reform is filled with complexities. Just to name a few are the politics, the body of law and policy and often the use of terms that only add confusion. During the 2007 immigration debate, I recall the term “clay pigeon” (a Senate floor procedure) confused even the experts. Right now, the term that is turning heads is “Queen-of-the-Hill”. So why does it matter you ask? Well let me explain.

A bipartisan group in the House has called on leaders to consider a proposal for a "Queen-of-the-Hill" (most votes wins) immigration rule (H. Res. 774) and urge action to vote on a legislative solution for the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program. SHRM and CFGI are members of the coalition for the American Dream which issued a press statement in support of action.

A vote on this issue matters because earlier in the year votes in the Senate failed. Right now, 190 Democrats and 50 Republicans in the House (a majority of the House) support H. Res. 774 and a debate and vote on immigration DACA related proposals. If Congress, could begin to move proposals forward there might be a chance (if even a small chance) to break the logjam on immigration reform.

Specifically, "Queen-of-the-Hill' is a House procedure that has not been used since 2015. The procedure would require separate votes and consideration of (four immigration) proposals on the House floor and members could vote in support of as many proposals as they want. The proposal that receives the greatest number of votes would be adopted. If none of the proposals receive a majority-of-the-votes, then none of the proposals would be adopted.

The proposals that would get a vote under H. Res. 774 include:

- The Securing America's Future Act (HR 4760), a bill that would allow DACA recipients to apply for three years of work authorization and deferred deportation that may be extended if they qualify. The bill also includes other provisions like mandatory E-Verify, historical limits to family sponsored green cards, a reallocation of visas to employment-based green cards and a new agricultural guest worker program.

- The House DREAM Act (H.R. 3440), a bill that would allow DACA recipients and DACA eligible individuals to apply for work authorization and deferred deportation, legal permanent residence and a five- year path to citizenship if they qualify.

- The USA Act (H.R. 4796), a bill that would allow for DACA recipients and DACA eligible individuals to apply for work authorization and deferred deportation and legal permanent residence if they qualify.

- A yet to be unveiled bill from House Speaker Ryan (R-WI)

Whether there is any chance for success will be up to House leaders, as the House bipartisan group is asking leaders to support H. Res. 774. However, the resolution may be far from successful. House Speaker Ryan (R-WI) has publicly stated he does not believe it makes sense to bring a bill through a process that only produces something that would get vetoed by the president. In this scenario, it is possible that any immigration bill that could pass the House might not make it through the Senate let alone find support from the president.

Given, the president’s resistance to many DACA related proposals, perhaps in the end, he will be the “King” of this “Queen-of-the-Hill” strategy.

This article was written by Rebecca Peters of SHRM Blog on April 23rd, 2018.

The Cadillac Creep Will Impact Your Econo-Health Plan

How will the Cadillac tax affect you in the near future? From SHRM, get the details in this article.

As an HR Professional in 2010, I recall thinking, as I struggled to wrap my mind around the myriad of complex provisions included in the ACA, that the Cadillac tax was probably one provision that I didn’t need to concern myself with. After all, it was years in the future and only applied to those other, richer plans, right? Time for a fast forward reality-check.

The Cadillac tax has been delayed in the past but is set to begin in 2022 on high-cost employer-sponsored health coverage. It will tax health coverage that exceeds $10,200 for individual coverage and $27,500 for family coverage at the rate of 40%. This includes contributions made by employers and employees toward health coverage premiums but not cost-sharing amounts such as deductibles, coinsurance or co-payments made when care is delivered.

But, employers, like mine, have certainly not been idle during the last eight years. We have continued to work to design health care plans that will attract and retain top talent while ensuring that coverage meets minimum value and affordability requirements mandated by the ACA. All the while, health care costs, particularly driven by prescription drug costs, continue to climb. Studies suggest that prescription drugs will continue to represent a larger portion of the overall health spending. I have seen this firsthand with the employer-sponsored plans I manage where prescription drug costs may represent over 30% of total health claims spent.

This leaves employers with some tough decisions to either reduce the benefits they offer to maintain a cost-effective plan that still meets minimum coverage and affordability standards or absorb additional costs. And then, there’s the Cadillac creep. A monthly individual premium of $10,200 annually or $850 per month no longer seems far-fetched as I stare into a future where drug cost inflation rates outpace wage increases.

I’m a proud member of the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM), which encourages Congress to fully repeal the excise tax. I support and join in SHRM’s advocacy efforts to defeat this tax because over 178 million Americans get their health care through employer-sponsored health plans. We can’t afford to let the Cadillac creep impact employers and employees.

This article was written by Crystal Frey of SHRM Blog on April 20th, 2018.

The Opioid Epidemic and Medicaid’s Role in Facilitating Access to Treatment

The Kaiser Family Foundation has released the key findings in Medicaid's role in the opioid epidemic. Get the facts, statistics, and visual charts here.

Key Findings

In 2016, 1.9 million nonelderly adults in the United States had an opioid addiction. Medicaid covers 4 in 10 nonelderly adults with opioid addiction. This brief examines Medicaid’s role in facilitating access to treatment for opioid addiction. Key findings include:

- Among nonelderly adults with opioid addiction, those with Medicaid were twice as likely as those with private insurance or no insurance to have received treatment in 2016.

- Medicaid facilitates access to treatment by covering numerous inpatient and outpatient treatment services, as well as medications prescribed as part of medication-assisted treatment.

- States use Medicaid Section 1115 waivers and other program authorities to expand treatment options for enrollees with opioid addiction.

While additional states expanding Medicaid could increase coverage and access, support for new work and premium requirements could impose barriers to obtaining and maintaining Medicaid coverage that may compromise efforts to address the opioid crisis.

Introduction

The opioid epidemic continues to escalate, with 1.9 million nonelderly adults having an opioid addiction in 2016.1 Opioid addiction is often associated with comorbid physical and mental health conditions and high levels of health care services utilization. These issues have worsened throughout the past decade as the opioid epidemic has escalated. In 2016, there were 42,249 opioid overdose deaths in the United States, more than quadruple the number in 2001, and the number of deaths from heroin and fentanyl have surpassed the number due to prescription opioids. The Trump administration has stated that addressing the opioid epidemic is a key priority.

Medicaid has historically filled critical gaps in responding to public health crises, such as the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s, the Flint water crisis, and numerous natural disasters since the program originated. As with these other public health crises, Medicaid helps to address the opioid epidemic by providing access to coverage and necessary health care. The program covers a disproportionate share of individuals with opioid addiction and facilitates access to numerous treatment services. Additionally, as of February 2018, 33 states have adopted the Medicaid expansion, with enhanced federal funding, to cover adults up to 138% of the federal poverty level ($16,753/year for an individual in 2018). All Medicaid expansion benefit packages must include behavioral health services, including mental health and substance use disorder services, which has increased access to care for many people with opioid addiction.

Based on data from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, this brief describes nonelderly adults with opioid addiction, including their demographic characteristics and insurance statuses, and compares receipt of various treatment services among those with Medicaid to those with private insurance and those who are uninsured. It also describes Medicaid financing for opioid treatment and the ways in which Medicaid promotes access to treatment for enrollees with opioid addiction.

Characteristics of Nonelderly Adults with Opioid Addiction

Individuals with opioid addiction are predominantly white, male, and young. In 2016, nearly 3 in 4 (74%) nonelderly adults with opioid addiction were white (Figure 1). Those with opioid addiction were also more likely to be male (58%), although the epidemic has touched an increasingly large share of women in recent years, including many pregnant women.2,3 Additionally, nearly half (48%) were between ages 18 and 34, and another one-third (32%) were between ages 35 and 49. This age distribution is comparable to those for other types of addiction, including addictions to both drugs and alcohol, which generally affect young adults more than they affect other age groups.4

Figure 1: Race, Gender, and Age of Nonelderly Adults with Opioid Addiction, 2016

The majority of nonelderly adults with opioid addiction are employed, but many have low incomes. In 2016, nearly 6 in 10 (56%) were employed; however, there was wide variability with regard to the types of jobs and industries in which they work, their salaries, and the number of hours they worked each week (Figure 2). Of those who were employed, about 7 in 10 (72%) reported working at a full-time job during the previous week.5 One in ten were unemployed and an additional 13% were unable to work because of a disability, reflecting the complicated health needs of individuals with opioid addiction, many of whom may have developed an addiction to opioids after using opioids to treat their chronic pain.6 Adults with opioid addiction are also more likely than other adults to have many other health conditions, including hepatitis, HIV, and mental illness,7 all of which may hinder their ability to work. As a result of these and other factors, more than half of nonelderly adults with opioid addiction had low incomes in 2016, and over a quarter (28%) lived below the poverty line (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Employment Status and Income of Nonelderly Adults with Opioid Addiction, 2016

Medicaid covers a disproportionate share of nonelderly adults with opioid addiction, and an even greater share of those with low incomes. In 2016, nearly 4 in 10 (38%) were covered by Medicaid and a similar share (37%) had private insurance. Approximately 1 in 6 (17%) was uninsured (Figure 3). Low-income nonelderly adults with opioid addiction are typically less likely than adults with higher incomes to have jobs that offer health insurance.8 In 2016, over half (55%) were covered by Medicaid, while only 13% had private insurance. Nearly 1 in 4 (24%) were uninsured (Figure 3), although if they lived in states that expanded Medicaid, they would likely be eligible for coverage.

Figure 3: Insurance Status of Nonelderly Adults with Opioid Addiction, 2016

Utilization of Opioid Addiction Treatment Services

Overall receipt of treatment for opioid addiction is low. In 2016, fewer than 3 in 10 (29%) adults with opioid addiction received any treatment for their addiction (Figure 4).9 Opioid addiction treatment can be delivered in an inpatient or outpatient setting and can be provided in numerous types of facilities, including hospitals, drug or alcohol rehabilitation facilities (for either inpatient or outpatient services), mental health centers, or private doctors’ offices. Depending on the severity of their addictions, some patients begin in an inpatient facility and then later transition to an outpatient setting, while others require only outpatient treatment. Overall, in 2016, 16% of nonelderly adults with opioid addiction received inpatient treatment, while 25% received outpatient treatment.

Figure 4: Past-Year Opioid Addiction Treatment Among Nonelderly Adults with Opioid Addiction by Insurance Status, 2016

Among nonelderly adults with opioid addiction, those with Medicaid are significantly more likely than those with private insurance or those who are uninsured to receive treatment. In 2016, those with Medicaid were twice as likely as those with private insurance or no insurance to receive any treatment for their addiction (43% vs. 21% and 23%). Nearly a quarter of adults with opioid addiction who had Medicaid coverage received inpatient care, while nearly 4 in 10 received outpatient care. In contrast, just over 1 in 10 (13%) of those with private insurance received any inpatient treatment and only 17% received any outpatient treatment. Those who were uninsured received treatment at rates similar to those with private insurance. These differences in utilization highlight the significant role Medicaid plays in increasing access to treatment.

Figure 5: Past-Year Outpatient Addiction Treatment Among Nonelderly Adults with Opioid Addiction by Insurance Status, 2016

Adults with opioid addiction who were covered by Medicaid were significantly more likely to have received treatment at an outpatient rehabilitation center or at an outpatient mental health center than those with private insurance or those who were uninsured (Figure 5). In 2016, adults with opioid addiction covered by Medicaid were three times more likely to have received treatment at these facilities than privately insured or uninsured adults. At the same time, utilization of services at private physician’s offices did not differ significantly across the three groups. Higher rates of utilization of outpatient treatment services by those with Medicaid may reflect the greater push for outpatient community-based behavioral health treatment in recent decades.10

Medicaid’s Role in Covering Opioid Addiction Treatment Services

State Medicaid programs cover numerous addiction treatment services that fit into several state plan categories, including outpatient treatment, inpatient treatment, prescription drugs, and rehabilitation. The standard of care for opioid addiction is medication-assisted treatment (MAT), which combines one of three medications (methadone, buprenorphine, or naltrexone) with counseling and other support services. All state Medicaid programs cover at least one medication used as part of MAT,11 and most cover all three of these medications. State Medicaid programs also cover many counseling and other support services, delivered either as part of MAT or separately. Most of these services are delivered at state option and include detoxification, intensive outpatient treatment, psychotherapy, peer support, supported employment, partial hospitalization, and inpatient treatment.12

Several policy changes have allowed states to obtain waivers to allow Medicaid funding of substance use treatment services at institutions for mental disease (IMDs). Federal law has historically prohibited Medicaid payments for services provided to adults age 21-64 in IMDs as a way to preserve state financing of these services. However, in April 2016, CMS issued final Medicaid managed care regulations that allow federal matching funds for managed care capitation payments for services in an IMD for up to 15 days in a month in lieu of services covered under the state plan and at the enrollee’s option.13 Additionally, in July 2015, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) released guidance stating that states could request federal funding for substance use disorder services delivered to nonelderly adults in IMDs through Section 1115 demonstration waivers. On November 1, 2017, CMS issued revised guidance that continues to allow states to seek Section 1115 waivers to pay for services provided in IMDs, including substance use disorder services. A number of states have sought waivers of the IMD exclusion specifically to expand treatment options for substance use disorder services. As of March 2018, CMS has approved waiver requests in 10 states to provide substance use disorder services in an IMD, and 10 states have waiver applications pending with CMS.14

Many states have also applied for other Medicaid Section 1115 behavioral health waivers focused on treating individuals with addiction, including opioid addiction. CMS has approved community-based benefit expansions proposed in Section 1115 waivers, which enable states to provide additional services to individuals with addiction, such as supportive housing, supported employment (such as job coaching), and peer recovery coaching. Additionally, CMS has approved waivers that allow states to expand Medicaid eligibility to cover additional populations with behavioral health needs, to provide home and community-based services, and to implement certain delivery system reforms, such as physical and behavioral health integration and alternative payment models.

Because of the large number of Medicaid enrollees with opioid addiction and the breadth of treatment services that Medicaid covers, Medicaid finances a substantial proportion of addiction treatment. In 2014, Medicaid financed 21% of all addiction treatment, which was more than the share covered by all private insurers combined (18%). Nine percent of all spending on addiction treatment came from out-of-pocket payments (Figure 6).15

Figure 6: Proportion of Total Spending on Addiction Treatment Services in 2014, by Payer

Looking Ahead

Medicaid plays a major role in facilitating access to inpatient and outpatient treatment services for individuals with opioid addiction. Nonelderly adults with Medicaid were more likely than those without insurance to receive various types of opioid addiction treatment and had better access to treatment than those with private insurance. Furthermore, despite the IMD payment exclusion, individuals with Medicaid were more likely than privately insured individuals to receive inpatient treatment.

As the opioid epidemic continues to worsen, particularly as fentanyl has become more pervasive,16 states are increasingly looking to Medicaid to expand treatment options to stem the crisis. In addition to covering MAT medications and numerous other treatment services, states are seeking waivers to allow payment for opioid treatment services provided in IMDs, to expand coverage of community-based benefits to support treatment and recovery, and better integrate behavioral health services, including substance use disorder services, with physical health services.

Non-expansion states can improve access to treatment by expanding Medicaid, which would enable them to cover many people with opioid addiction who are currently uninsured. At the same time, using 1115 waivers to impose new requirements in Medicaid, including work requirements and premiums, could compromise efforts to address the opioid epidemic. Although some states exempt people in addiction treatment from work requirements and other states count treatment as work hours, other states do not have such exemptions. Additional reporting requirements coupled with new premium requirements may also make it more difficult for eligible individuals to enroll in Medicaid and for those currently enrolled to keep their coverage. Utilization of treatment by adults with an opioid addiction is already low; imposing new barriers to obtaining and maintaining Medicaid could further impede those battling opioid addiction from getting the care they need.

This article was brought to you from the Kaiser Family Foundation on April 11,2018.

Taking Action to Prevent the Harmful Impact of Short-Term Plans

This article explores the recently established rule on short-term limited duration plans - as proposed by HHS - which would not comply with consumer protections afforded under ACA.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has proposed a new rule, open for comment until April 23, 2018, that is dangerous to consumers and to health care marketplaces. This rule would expand the sale of “short-term limited duration plans” that do not have to comply with the consumer protections afforded under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and often leave consumers uncovered for major medical expenses.

The short-term plan rule will harm consumers and health care markets

The proposed rule would alter the definition of short-term plans as a backdoor way of creating a new class of plans that do not have to comply with the ACA, extending the duration of short-term plans from policies that last for 3 months to policies that can last just short of one year. Under this rule, insurers may also be allowed to renew a short-term plan for an enrollee after that period is up.

Companies selling these plans can make large profits at consumers’ expense, and the plans do not have to cover pre-existing conditions, provide essential health benefits, include adequate provider networks, or comply with a host of other key protections, as we describe in Seven Reasons the Trump Administration's Short-Term Health Plans Are Harmful to Families. Moreover, if many young and healthy people are drawn into these plans, the plans will undermine the market for real coverage, driving up prices in the ACA-compliant marketplace.

Now is the time to take action to prevent short-term plans from harming consumers and insurance markets throughout the country. Here we outline how advocates, consumers, and states can take action to address this harmful rule.

Stakeholders can urge HHS to stop the spread of harmful short-term plans

It’s important that HHS hears from stakeholders all over the country about how short-term plans will leave those who enroll in them without adequate protection from the costs of care, and how those who seek to stay in the market for comprehensive coverage will experience spikes in premiums and jeopardized access to coverage if short-term plans are allowed to expand.

The short-term plan rule will also burden states and insurance companies that are interested in making comprehensive coverage affordable. Particularly if the rule allows the proliferation of short-term plans that last for up to 12 months to take effect after insurers have already planned their premium pricing for 2019, these plans will cause chaos for comprehensive insurance providers and states alike in maintaining a stable insurance market. These expanded short-term plans should not be put on the market at all, but at the very least HHS should delay implementation of the final rule to give states and insurers more time to plan for it to take effect.

Advocates, consumers, state officials, health care providers, and other stakeholders can all make a difference by commenting to HHS about these problems. Stakeholders can also make a difference by urging state policymakers and officials to comment on the rule as well. Comments should urge HHS to stop or at the very least delay implementation of the rule on short-term plans. Comments should be submitted here by 5 PM on Monday, April 23rd.

States can take direct action to protect against short-term plans