How to Respond to the Spread of Measles in the Workplace

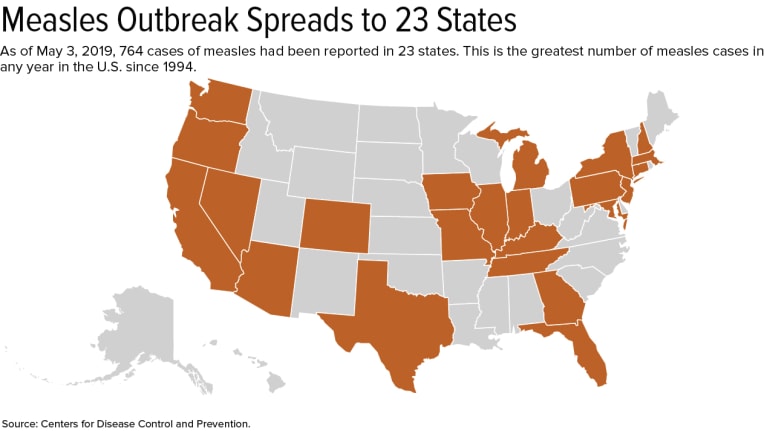

How should employers respond to the spread of measles? With measles now at its highest number of cases in one year since 1994, employers are having to cooperate with health departments to fight the spread. Read this blog post from SHRM to learn more.

Employers and educators are cooperating with health departments to fight the spread of measles, now at its highest number of cases in one year since 1994: 764.

Two California universities—California State University, Los Angeles (Cal State LA) and the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA)—recently quarantined staff and students at the request of local health departments.

In April at Cal State LA, the health department told more than 600 students and employees to stay home after a student with measles entered a university library.

Also last month, UCLA identified and notified more than 500 students, faculty and staff who may have crossed paths with a student who attended class when contagious. The county health department quarantined 119 students and eight faculty members until their immunity was established.

The quarantines ended April 30 at UCLA and May 2 at Cal State LA.

Measles is one of the most contagious viruses; one measles-infected person can give the virus to 18 others. In fact, 90 percent of unvaccinated people exposed to the virus become infected, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) notes.

Action Steps for Employers

Once an employer learns someone in the workplace has measles, it should immediately send the worker home and tell him or her not to return until cleared by a physician or other qualified health care provider, said Robin Shea, an attorney with Constangy, Brooks, Smith & Prophete in Winston-Salem, N.C.

The employer should then notify the local health department and follow its recommended actions, said Howard Mavity, an attorney with Fisher Phillips in Atlanta. The company may want to inform workers where and when employees might have been exposed. If employees were possibly exposed, the employer may wish to encourage them to verify vaccination or past-exposure status, directing those who are pregnant or immunocompromised to consult with their physicians, he said.

Do not name the person who has measles, cautioned Katherine Dudley Helms, an attorney with Ogletree Deakins in Columbia, S.C. "Even if it is not a disability—and we cannot assume that, as a general rule, it is not—I believe the ADA [Americans with Disabilities Act] confidentiality provisions cover these medical situations, or there are situations where individuals would be covered by HIPAA [Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act]."

The employer shouldn't identify the person even if he or she has self-identified as having measles, Mavity noted.

Shea said that once the person is at home, the employer should:

- Inform workers about measles, such as symptoms (e.g., dry cough, inflamed eyes, tiny white spots with bluish-white centers on a red background in the mouth, and a skin rash) and incubation period—usually 10 to 12 days, but sometimes as short as seven days or as long as 21 days, according to the CDC.

- Inform employees about how and where to get vaccinations.

- Remind workers that relatives may have been indirectly exposed.

- Explain that measles exposure to employees who are pregnant or who might be pregnant can be harmful or even fatal to an unborn child.

- Explain that anyone born before 1957 is not at risk. The measles vaccine first became available in 1963, so those who were children before the late 1950s are presumed to have been exposed to measles and be immune.

Employers may also want to bring a health care provider onsite to administer vaccines to employees who want or need them, Shea said.

"Be compassionate to the sick employee by offering FMLA [Family and Medical Leave Act] leave and paid-leave benefit options as applicable," she said.

When a Sick Employee Comes to Work Anyway

What if an employee insists on returning to work despite still having the measles?

Mavity said an employer should inform the worker as soon as it learns he or she has the measles to not return until cleared by a physician, and violating this directive could result in discipline, including discharge. A business nevertheless may be reluctant to discipline someone who is overly conscientious, he said. It may opt instead to send the employee home if he or she returns before being given a medical clearance.

The employer shouldn't make someone stay out longer than is required, Helms said. Rely instead on the health care provider's release.

SOURCE: Smith, A. (9 May 2019) "How to Respond to the Spread of Measles in the Workplace" (Web Blog Post). Retrieved from https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/legal-and-compliance/employment-law/pages/how-to-respond-spread-measles-workplace.aspx

Can Employers Require Measles Vaccines?

Can employers require that their employees get the measles vaccine? The recent measles outbreak is raising the question of whether employers can require that their workers get the vaccine. Read this blog post from SHRM to learn more.

The recent measles outbreak, resulting in mandatory vaccinations in parts of New York City, raises the question of whether employers can require that workers get the vaccine to protect against measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) or prove immunity from the illness.

The answer generally is no, but there are exceptions.

Offices and manufacturers probably can't require vaccination or proof of immunity because the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) generally prohibits medical examinations—unless the employer is in a location like Williamsburg, the neighborhood in Brooklyn where vaccinations are now mandatory. Health care providers, schools and nursing homes, however, probably can require them because their employees work with patients, children and people with weak immune systems who risk health complications from measles.

But even these employers must try to find accommodations for workers who object to vaccines for a religious reason or because of a disability that puts them at risk if they're vaccinated, such as having a weak immune system.

Proof of Immunity

Proof of immunity includes one of the following:

- Written documentation of adequate vaccination.

- Laboratory evidence of immunity.

- Laboratory confirmation of measles.

- Birth before 1957. The measles vaccine first became available in 1963, so those who were children before the late 1950s are presumed to have been exposed to measles and be immune.

Measles, which is contagious, typically causes a high fever, cough and watery eyes, and then spreads as a rash. Measles can lead to serious health complications, especially among children younger than age 5. One or two out of 1,000 people who contract measles die, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

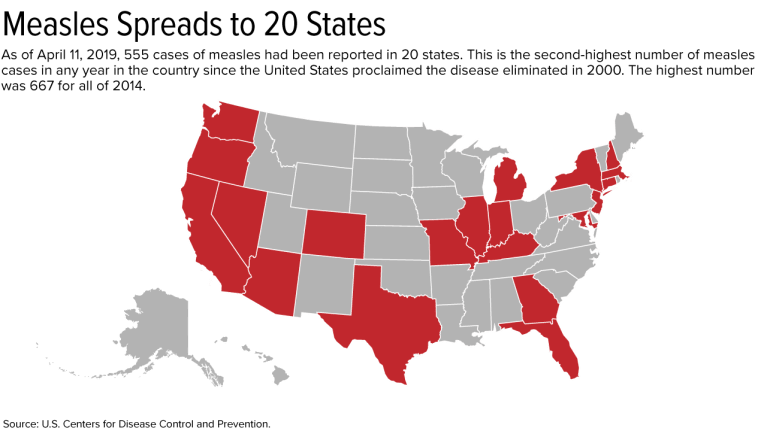

Outbreak Has Spread to 20 States

As of April 11, 555 cases have been reported in the United States this year. This is the second-greatest number in any year since the United States proclaimed measles eliminated in 2000; 667 cases were reported in all of 2014.

On April 9, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio declared a public health emergency in Williamsburg, requiring the MMR vaccine in that neighborhood. Those who have not received the MMR vaccine or do not have evidence of immunity may be fined $1,000.

Since the outbreak started, 285 cases have been confirmed in Williamsburg, including 21 hospitalizations and five admissions to intensive care units.

If a city requires vaccinations, an employer's case for requiring them is much stronger, said Robin Shea, an attorney with Constangy, Brooks, Smith & Prophete in Winston-Salem, N.C. But employers usually should not involve themselves in employees' health care unless they are making an inquiry related to a voluntary wellness program, or the health issue is job-related, she cautioned.

The measles outbreak has spread this year to 20 states—outbreaks linked to travelers who brought measles to the U.S. from other countries, such as Israel, Ukraine and the Philippines, where there have been large outbreaks.

Strike the Right Balance

Health care employers typically require vaccinations or proof of immunity as a condition of employment, said Howard Mavity, an attorney with Fisher Phillips in Atlanta. He noted that most schoolchildren must be immunized, so many employees can show proof of immunity years later.

If an employee provides current vaccination records when an employer asks, the ADA requires that those records be kept in separate, confidential medical files, noted Meredith Shoop, an attorney with Littler in Cleveland.

All employers must balance their health and safety concerns with the right of employees with disabilities to reasonable accommodations under the ADA and the duty to accommodate religious workers under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Under the ADA, a reasonable accommodation is required unless it would result in an undue hardship or direct threat to the safety of the employee or the public. The direct-threat analysis will be different for a registered nurse than for someone in a health care provider's billing department, for example, who might not work around patients.

Even if the ADA permitted mandatory vaccines in a manufacturing setting in limited circumstances, such as in Williamsburg now, any vaccination orders may need to be the subject of collective bargaining if the factory is unionized. Shoop has seen manufacturers shut down because employees were reluctant to come to work when their co-workers were sick on the job.

An employer does not have to accommodate someone who objects to a vaccine merely because he or she thinks it might do more harm than good but doesn't have an ADA disability or religious objection, said Kara Shea, an attorney with Butler Snow in Nashville, Tenn.

If someone claims to have a health condition that makes getting vaccinated a health risk, the employer does not have to take the person's word for it. The employer instead should ask the person to sign a consent form allowing the employer to learn about the condition and get documentation from the employee's doctor, she said. Before accommodating someone without an obvious impairment, the ADA allows employers to require medical documentation of the disability.

Courts don't closely scrutinize religious objections to immunizations, Mavity remarked.

"Some people have extremely strong beliefs that they don't want a vaccine in their body," said Kathy Dudley Helms, an attorney with Ogletree Deakins in Columbia, S.C. If the employer works with vulnerable people but can't find an accommodation for a worker who refuses vaccination, the employee may have to work elsewhere, she said.

SOURCE: SHRM (17 April 2019) "Can Employers Require Measles Vaccines?" (Web Blog Post). Retrieved from https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/legal-and-compliance/employment-law/pages/measles-outbreak-2019-vaccinations.aspx

HR’s recurring headache: Convincing employees to get a flu shot

According to The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, the flu cost U.S. companies billions of dollars in medical fees and lost earnings. Read this blog post to learn how HR departments are convincing their employees to get a flu shot.

Elizabeth Frenzel and her team are the Ford assembly line of flu shots: They can administer about 1,800 flu shots in four hours.

Frenzel is the director of employee health and wellbeing at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, and with 20,000 employees, she is no stranger to spearheading large flu shot programs. The center where Frenzel administers flu shots has roughly a 96% employee vaccination rate. Back in 2006, only about 56% of employees got their shots.

“When you run these large clinics, safety is critically important,” she says.

Problems like Frenzel’s are not unique. Every fall, HR departments send mass emails encouraging employees to get vaccinated. The flu affects workforces across the country, costing U.S. companies billions of dollars in medical fees and lost earnings, according toThe National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. It is not only a cause of absenteeism but a sick employee can put their coworkers at risk. Last year the flu killed roughly 80,000 people, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

Even if an employer offers a flu shot benefit, the push to get employees to sign up for the vaccine can be a two-month slough, with reminder emails going unanswered. Moreover, companies often contend with misconceptions about the shot, such as the popular fallacy that shots will make you sick, running out of the vaccine, and sometimes just plain employee laziness.

In Frenzel’s case, increasing the number of employees who got flu shots weren’t just a good idea, but it was needed to protect the lives of the cancer patients they interact with every day. The most startling fact, she says, was that healthcare workers who interact with patients daily were less likely to get vaccinated.

“So that’s how we started down the path,” she says. “Really targeting these people who had the closest patient contact.”

Frenzel credits the significant increase in employee participation in the flu shot program to several factors. They made the program mandatory — a common move in the healthcare industry — but Frenzel says their improvement also was related to flu shot education. The center made it a priority to explain to staff members exactly why they should get vaccinated. Frenzel made it more convenient, offering the vaccine at different hours of the day, so all employees could fit it into their schedule. They also made it fun, offering stickers for employees to put on their badge once they got a shot. Every year, she says, they pick a new color.

Employers outside of the medical industry are focused on improving their flu shot programs, including Edward Yost, manager of employee relations and development at the Society for Human Resource Management, who helped organize a health fair and flu shot program for 380 employees.

Yost says onsite flu shot programs are more effective than vouchers that allow employees to get vaccinated at a primary care doctor or pharmacy. The more convenient you make the program, he says, the more likely employees will use it.

“There’s no guarantee that those vouchers are going to be used,” he says. “Most people aren’t running out to a Walgreens or a CVS saying, please stab me in the arm.”

Besides the convenience, employees are more likely to sign up for a shot when they see co-workers getting vaccinated, Yost says. If a company decides to offer an onsite program, planning ahead is key. Sometimes employees will not sign up in advance for the vaccine but then decide they want to get one once the vendor arrives onsite. Yost recommends companies order extra vaccines.

“Make sure that you’re building in the expectation that there's going to be at least a handful of folks who are more or less what you call walk-ins in that circumstance,” he says.

Incentivizing employees to get the flu shot is also important, Yost says. Some firms will offer a gym membership or discounted medical premiums if they attend regular checkups and get a biometric screening in addition to a flu shot. He recommends explaining to employees how a vaccine can help reduce the number of sick days they may use.

“Employees need to see that there’s something in it for them,” Yost says. “And quite honestly, being sick is a miserable thing to experience.”

Affiliated Physicians is one of the vendors that can come in and administer flu shots in the office. The company has provided various employers with vaccines for more than 30 years, including SourceMedia, the parent company of Employee Benefit News andEmployee Benefit Adviser. In the past 15 years, Ari Cukier, chief operating officer of the company, says there’s been an increase in the amount of smaller companies signing up for onsite vaccines. HR executives should be aware of the number of employees signing up for vaccinations when scheduling an onsite visit.

“We can’t go onsite for five shots, but 20-25 shots and up, we’ll go,” Cukier says.

Cukier agrees communication between human resources departments and employees is crucial in getting people to sign up for shots. Over the years, he’s noticed that more people tend to sign up for shots based on the severity of the previous flu season.

“Last year, as bad as it was, we have seen a higher participation this year,” he says.

Brett Perkison, assistant professor of occupational medicine at the University of Texas School of Public Health in Houston, says providing a good flu shot program starts from the top down. The company executives, including the CEO and HR executives, should set an example by getting and promoting the shots themselves, he says.

It’s also important to listen to employee concerns. Before implementing a program, if workers are taking issue with the shot, it’s best to hold focus groups to alleviate any worries before the shots are even being administered, he says.

Some employees may even believe misconceptions like the flu shot will make one sick or lead to long-term illnesses, he says. Others may question the effectiveness of the shot. Having open lines of communication with employees to address these concerns will ensure that more will sign up, Perkison says.

Regardless of the type of flu shot program, the most important part is preventing illness, SHRM’s Yost says. While missing work and losing money are important consequences of a flu outbreak, having long-term health issues is even more serious, he says. Plus, no one likes being sick.

“Who’s going to argue about that?” he says.

This article originally appeared in Employee Benefit News.

SOURCE: Hroncich, C (24 October 2018) "HR’s recurring headache: Convincing employees to get a flu shot" (Web Blog Post). Retrieved from https://www.employeebenefitadviser.com/news/hrs-recurring-headache-convincing-employees-to-get-a-flu-shot