U.S. Obesity Rate Climbing in 2013

Originally posted November 1, 2013 by Lindsey Sharpe on https://www.gallup.com

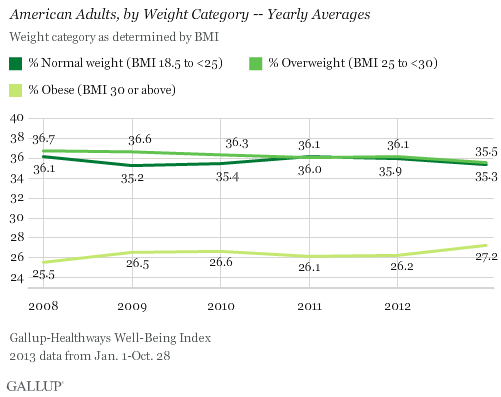

WASHINGTON, D.C. -- The adult obesity rate so far in 2013 is 27.2%, up from 26.2% in 2012, and is on pace to surpass all annual average obesity rates since Gallup-Healthways began tracking in 2008.

The one-percentage-point uptick in the obesity rate so far in 2013 is statistically significant and is the largest year-over-year increase since 2009. The higher rate thus far in 2013 reverses the lower levels recorded in 2011 and 2012, and is much higher than the 25.5% who were obese in 2008.

The increase in obesity rate is accompanied by a slight decline in the percentage of Americans classified as normal weight or as overweight but not obese. The percentage of normal weight adults fell to 35.3% from 35.9% in 2012, while the percentage of adults who are overweight declined to 35.5% from 36.1% in 2012. An additional 1.9% of Americans are classified as underweight in 2013 so far.

Since 2011, U.S. adults have been about as likely to be classified as overweight as normal weight. Prior to that, Americans were most commonly classified as overweight.

Gallup and Healthways began tracking Americans' weight in 2008. The 2013 data are based on more than 141,000 interviews conducted from Jan. 1 through Oct. 28 as part of the Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index. Gallup uses respondents' self-reported height and weight to calculate body mass index (BMI) scores. Individual BMI values of 30 or above are classified as "obese," 25 to 29.9 are "overweight," 18.5 to 24.9 are "normal weight," and 18.4 or less are "underweight."

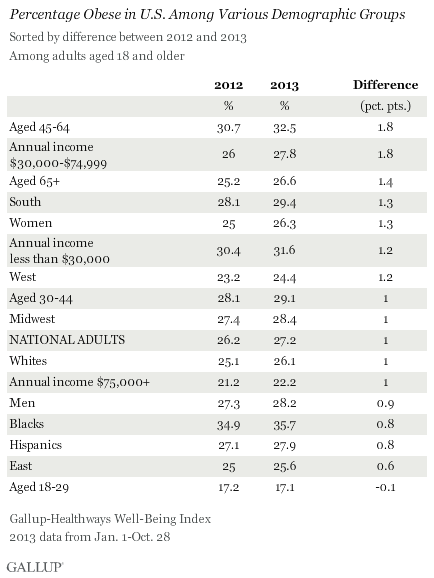

Obesity Rates Increase Across Almost All Demographic Groups

Obesity rates have increased at least slightly so far in 2013 across almost all major demographic and socioeconomic groups. One exception is 18- to 29-year-olds, among whom the percentage who are obese has remained stable. The largest upticks between 2012 and 2013 were among those aged 45 to 64 and those who earn between $30,000 and $74,999 annually. The obesity rate within both groups increased by 1.8 points, which exceeds the one-point increase in the national average.

At 35.7%, blacks continue to be the demographic group most likely to be obese, while those aged 18 to 29 and those who earn over $75,000 annually continue to be the least likely to be obese.

Bottom Line

The U.S. obesity rate thus far in 2013 is trending upward and will likely surpass all annual obesity levels since 2008, when Gallup and Healthways began tracking. It is unclear why the obesity rate is up this year, and the trend since 2008 shows a pattern of some fluctuation. This underscores the possibility that that the recent uptick is shorter-term, rather than a more permanent change. Still, if the current trend continues for the next several years, the implications for the health of Americans and the increased burden on the healthcare system could be significant.

Blacks, those who are middle-aged, and lower-income adults continue to be the groups with the highest obesity rates. The healthcare law could help reduce obesity among low-income Americans if the uninsuredsign up for coverage and take advantage of the free obesity screening and counseling that most insurance companies are required to provide under the law.

Employers can also take an active role to help lower obesity rates. Gallup has found that the annual cost for lost productivity due to workers being above normal weight or having a history of chronic conditions ranges from $160 million among agricultural workers to $24.2 billion among professionals. Thus, employers can cut healthcare costs by developing and implementing strategies to help workers maintain or reach a healthy weight.

Gallup has also found that employees who are engaged in their work eat healthier and exercise more. Therefore, employers who actively focus on improving engagement may see healthier and more productive workers, in addition to lower healthcare costs.

About the Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index

The Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index tracks well-being in the U.S. and provides best-in-class solutions for a healthier world. To learn more, please visit well-beingindex.com.

Results are based on telephone interviews conducted as part of the Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index survey Jan. 1-Oct. 28, 2013, with a random sample of 141,935 adults, aged 18 and older, living in all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia.

For results based on the total sample of national adults, one can say with 95% confidence that the margin of sampling error is ±0.5 percentage points.

Interviews are conducted with respondents on landline telephones and cellular phones, with interviews conducted in Spanish for respondents who are primarily Spanish-speaking. Each sample of national adults includes a minimum quota of 50% cellphone respondents and 50% landline respondents, with additional minimum quotas by region. Landline and cellphone numbers are selected using random-digit-dial methods. Landline respondents are chosen at random within each household on the basis of which member had the most recent birthday.

Samples are weighted to correct for unequal selection probability, nonresponse, and double coverage of landline and cell users in the two sampling frames. They are also weighted to match the national demographics of gender, age, race, Hispanic ethnicity, education, region, population density, and phone status (cellphone only/landline only/both, and cellphone mostly). Demographic weighting targets are based on the March 2012 Current Population Survey figures for the aged 18 and older U.S. population. Phone status targets are based on the July-December 2011 National Health Interview Survey. Population density targets are based on the 2010 census. All reported margins of sampling error include the computed design effects for weighting.

In addition to sampling error, question wording and practical difficulties in conducting surveys can introduce error or bias into the findings of public opinion polls.

For more details on Gallup's polling methodology, visit www.gallup.com.

Learn How Inflammation Can Lead to Chronic Diseases

By Dr. Ann Kulze, M.D.

Inflammation is now widely recognized as a primary driver for most all chronic diseases and it appears that losing even modest amounts of weight can effectively douse the damaging inferno of excess inflammation in the body. For this one year evaluation, 438 women were placed on a weight loss program through diet or diet and exercise. For women in the diet and exercise group, measures of C-reactive protein (a key marker for inflammation in the body) dropped 42%. In the diet only group, levels dropped by 36 percent. For both groups, losing just 5% of their initial body weight provided even larger reductions in C-reactive protein. Because higher levels of C-reactive protein have been linked to a litany of chronic diseases including heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and cancers of the breast, colon, lung and uterus, this study underscores the enormous benefits that can result from losing even small amounts of excess body fat.

Joggers Rejoice!

Source: Dr. Ann Kulze

May 2012 Newsletter

Wellness Delivered Pure and Simple

In a stunning affirmation of the profound health-boosting effects of regular physical activity, European Cardiovascular researchers concluded that regular jogging can dramatically increase life expectancy. As part of the Copenhagen City Heart Study, investigators followed 19,329 adult study subjects over a period of up to 35 years. Study subjects who reported regular jogging at a "slow or average" pace were 40% less likely to die over the study period than non-joggers and increased their life expectancy by an average of 6 years. What's more, regular joggers also reported an enhanced sense of overall well-being.

Based on this evaluation, maximum survival benefits were seen in those who jogged between one to two and a half hours a week over two to three sessions. Thankfully, there are numerous types of aerobic activities that get the heart rate into this "jogging zone". According to the lead investigator, the goal is to move to the point of "feeling a little breathless, but not very breathless". (1)

Are Chubby Workers Eating You Out of Profits?

Source: https://safetydailyadvisor.blr.com

OSHA recordkeeping and reporting requirements appear straightforward, but the devil is in the details. Pound for pound, obese workers cost you plenty. Here are some facts that should disturb you.

| Which employee health issue costs employers more, obesity or smoking?

If you guessed obesity, you guessed right. A study in the Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine analyzed the additional costs of smoking and obesity among more than 30,000 Mayo Clinic employees and retirees. All had continuous health insurance coverage between 2001 and 2007. Both obesity and smoking were associated with excess health costs. Compared to nonsmokers, average health costs were $1,275 higher for smokers. And obese people averaged an additional $1,850 more than normal-weight individuals. For those with morbid obesity, costs were up to $5,500 per year. Clearly obesity is an issue that most employers will need to deal with in the future. Americans are becoming fatter every year, and that means increasing health problems and increasing health costs. Since many of these obese people work, employers will be impacted by increasing medical costs and lost productivity. Great news! BLR's renowned Safety.BLR.com® website now has even more timesaving features. Take our no-cost site tour! Or better yet, try it at no cost or obligation for a full 2 weeks. Facts and FiguresHere are some other statistics that paint a worrisome picture: • Annual healthcare cost of obesity in the U.S. is estimated to be $147 billion per year. • Annual medical burden of obesity increased to 9.1 percent in 2006 compared to 6.5 percent in 1998. • Medical expenses for an obese employee are estimated to be 42 percent higher than for employees with a healthy weight. • Three major conditions related to obesity (heart disease, diabetes and arthritis) cost employers $220 billion annually in medical cost and lost productivity, according to CDC and MetLife research. • An American Journal of Health Behavior study showed that the annual medical cost increased from $119 for normal-weight employees to $573 for overweight employees and to $620 for obese employees. • A MetLife study found that the average absence for employee who filed an obesity-related short-term disability claim was 45 days. • A 1998 study found obesity resulted in approximately 39 million lost work days, 239 million restricted-activity days, 90 million bed days and 63 million physician visits. • Obese employees have double workers’ compensation claims, 7 times higher medical claims, and lost 10 times more working days from illness or injury compared to non-obese employees, according to the Duke University Medical Center. Who's Obese?Obesity is defined as at least 30 to 40 pounds overweight, severely obese is at least 60 pounds overweight, and morbidly obese is at least 100 pounds overweight. Obesity can increase the risk for many adverse health effects, including: · Type-2 diabetes · Hypertension · Heart failure · High cholesterol · Kidney failure · Degenerative joint disease and arthritis · Gallstones and gall bladder disease · Cancer · Lung and breathing problems (asthma) · Faster aging |

New Guidelines On Obesity Treatment Herald Changes In Coverage

By Michelle Andrews

July 10, 2012

Source: Kaiser Health News

Eat less, exercise more. Simple? Yes. Easy? No. If weight loss were easy, obesity rates among adults in the United States probably wouldn't have reached the current 36 percent.

Recently revised guidelines from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force acknowledge that fact. They recommend that clinicians screen patients for obesity, which is defined as having a body mass index of 30 or higher. Further, they say patients who meet or exceed that level should be offered or referred to "intensive, multicomponent behavioral interventions" to help them lose weight.

The revised guidelines strengthen the previous recommendations, says David Grossman, a senior investigator at Group Health Research Institute in Seattle and a member of the task force.

For the millions of people who struggle to lose weight, the new guidelines offer much-needed support. It's unclear whether employers and insurers will welcome the change, though.

Under the 2010 health-care law, new health plans and those whose benefits change enough to lose their grandfathered status must provide services recommended by the Preventive Services Task Force at no cost to members. For the 70 percent of employers that already offer weight management programs, that may mean just supplementing what they already offer, says Russell Robbins, a senior clinical consultant at Mercer, a human resources consulting firm.

But some employers are concerned they may be on the hook for ongoing treatment as employees make repeated attempts to lose weight.

"From a financial standpoint, the guidelines are pretty broad and pretty extensive," says Helen Darling, president of the National Business Group on Health, which represents the interests of large firms. "Does this mean that employers and the government will be paying for up to 26 intense visits every year for every obese person for the rest of their lives?"

An HHS official said the department is evaluating whether to issue additional guidance on the new rules.

Insurers will be working to determine how best to satisfy the recommendations, says Susan Pisano, a spokeswoman for America's Health Insurance Plans, an industry group.

"I think the real question is making sure there are programs that fulfill these requirements," she says.

According to the task force, effective weight-loss programs involve 12 to 26 group or individual sessions over the course of a year that cover multiple behavioral management techniques. These may include setting weight-loss goals and strategizing about how to maintain lifestyle changes, incorporating exercise and eating a more healthful diet, and learning to address the psychological and other barriers that create roadblocks to weight loss. The task force found that people in these programs generally lost nine to 15 pounds in the first year.

The task force said there wasn't enough evidence to determine whether such interventions worked for people who were overweight but not obese.

A number of existing programs provide the kind of care that the guidelines recommend, say experts.

Weight Watchers, for example, runs 20,000 meetings a week around the country where people discuss their weight-loss challenges and successes and get pointers on losing weight and keeping it off.

At $42.95 a month for access to group meetings and online food tracking and other tools, however, it's not an option for many people with limited incomes, who make up a disproportionate share of the obese. Some employers subsidize their employees' membership in the program. Under the new guidelines, insurers and employers could be responsible for paying 100 percent of the cost.

Other programs have also been successful. Two years ago, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in partnership with UnitedHealth Group and the YMCA, launched the National Diabetes Prevention Program for people at high risk for developing Type 2 diabetes.

The program is based on a study in which participants who learned to eat more healthfully and exercised at least 150 minutes a week lost 5 to 7 percent of their weight and reduced their risk of developing diabetes by 58 percent.

The program is offered by many YMCAs and other groups. It offers each participant 16 weekly group weight-loss sessions followed by six monthly sessions. It's a covered benefit for people with UnitedHealthcare or Medica insurance; others pay based on a sliding scale, says Ann Albright, director of CDC's Division of Diabetes Translation. CDC is working with Medicaid and Medicare to try to get it covered by those programs, says Albright.

John Joseph IV tipped the scales at 203 and had a BMI of 28.3 when he paid $150 to join the program at the YMCA near his Birmingham, Ala., home. In the four months since then, the 34-year-old, who runs a job-coaching business for college grads, has dropped 17 pounds.

At the weekly group meetings, he learned to count the fat grams in food and to make smarter food choices. Now he eats fewer cookies and more flounder. He started an exercise program and runs or lifts weights for 30 minutes three times a week.

"I thought, if I can do this, it will give me the infrastructure and habits so I can get to the mid-170s, which is where I want to be," he says.

Losing weight is hard, but keeping it off may be harder.

In 2009, Gayenell Magwood lost 100 pounds with the help of the weight management center at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston.

But after health problems curtailed her exercise routine for a few months, her weight crept up to 170, a gain of nearly 20 pounds. Magwood, 49, who lives in North Charleston and is a researcher in the College of Nursing at MUSC, went through the 15-week program all over again, at a cost of about $600. She lost the weight she had regained.

Before enrolling in the MUSC program, "I'd never once been successful with significant weight loss," she says.

Obesity declining? Fat chance

LAURAN NEERGAARD, AP Medical Writer

Source: Timesleader.com

WASHINGTON — The obesity epidemic may be slowing, but don’t take in those pants yet.

Today, just over a third of U.S. adults are obese. By 2030, 42 percent will be, says a forecast released Monday.

That’s not nearly as many as experts had predicted before the once-rapid rises in obesity rates began leveling off. But the new forecast suggests even small continuing increases will add up.

“We still have a very serious problem,” said obesity specialist Dr. William Dietz of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Worse, the already obese are getting fatter. Severe obesity will double by 2030, when 11 percent of adults will be nearly 100 pounds overweight, or more, concluded the research led by Duke University.

That could be an ominous consequence of childhood obesity. Half of severely obese adults were obese as children, and they put on more pounds as they grew up, said CDC’s Dietz.

While being overweight increases anyone’s risk of diabetes, heart disease and a host of other ailments, the severely obese are most at risk — and the most expensive to treat. Already, conservative estimates suggest obesity-related problems account for at least 9 percent of the nation’s yearly health spending, or $150 billion a year.

Data presented Monday at a major CDC meeting paint something of a mixed picture of the obesity battle. There’s some progress: Clearly, the skyrocketing rises in obesity rates of the 1980s and ’90s have ended. But Americans aren’t getting thinner.

Over the past decade, obesity rates stayed about the same in women, while men experienced a small rise, said CDC’s Cynthia Ogden. That increase occurred mostly in higher-income men, for reasons researchers couldn’t explain.

About 17 percent of the nation’s children and teens were obese in 2009 and 2010, the latest available data. That’s about the same as at the beginning of the decade, although a closer look by Ogden shows continued small increases in boys, especially African-American boys.

Does that mean obesity has plateaued? Well, some larger CDC databases show continued upticks, said Duke University health economist Eric Finkelstein, who led the new CDC-funded forecast. His study used that information along with other factors that influence obesity rates — including food prices, prevalence of fast-food restaurants, unemployment — to come up with what he called “very reasonable estimates” for the next two decades.

Part of the reason for the continuing rise is that the population is growing and aging. People ages 45 to 64 are most likely to be obese, Finkelstein said.

Today, more than 78 million U.S. adults are obese, defined as having a body-mass index of 30 or more. BMI is a measure of weight for height. Someone who’s 5-feet-5 would be termed obese at 180 pounds, and severely obese with a BMI of 40 — 240 pounds.

The new forecast suggests 32 million more people could be obese in 2030 — adding $550 billion in health spending over that time span, Finkelstein said.

“If nothing is done, this is going to really hinder efforts to control health care costs,” added study co-author Justin Trogdon of RTI International.